Beginners guide to Amiga Basic

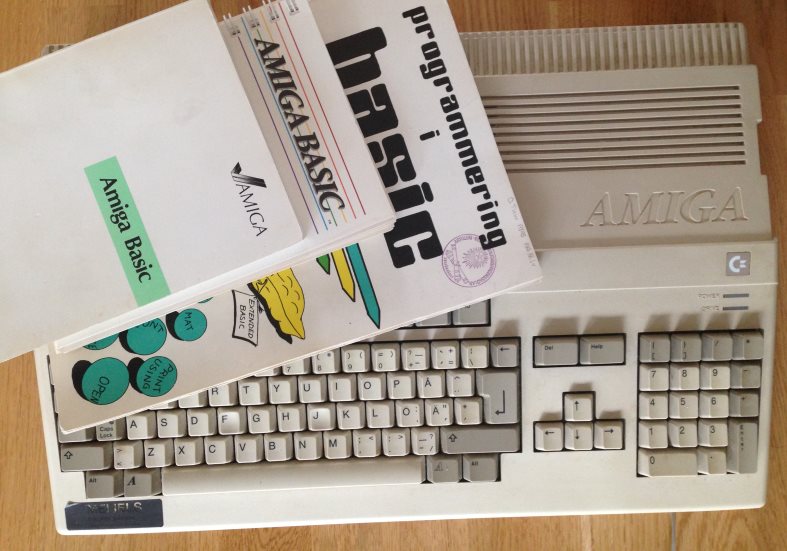

I suddenly found this urge to dig up my old Amiga and play around with it. I called up my parents and went over to their house. What I assumed was an Amiga and a screen, was boxes upon boxes of floppys, cords and other junk. What I also found in there was three books on Amiga Basic programming which inspired me to write this blog post1.

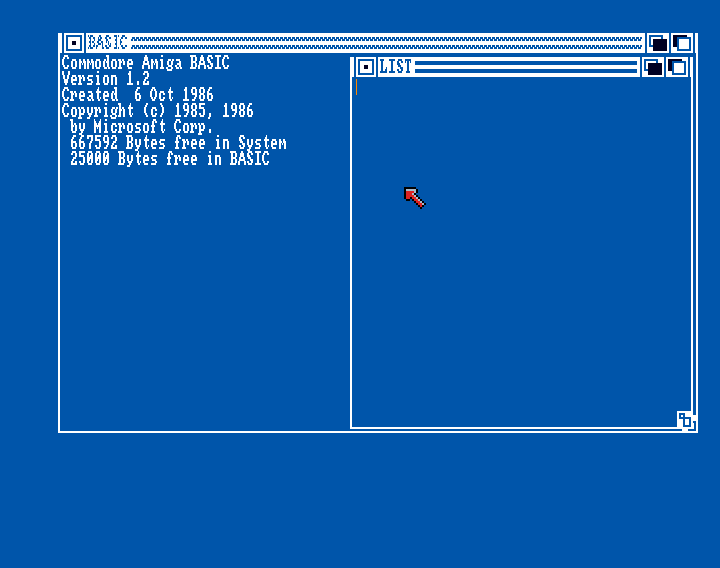

Amiga Basic was shipped with the operating system Workbench version 1.1-1.32. When Amiga OS 2.0 was released in 1990 Amiga Basic became obsolete. It had a bug preventing it from working properly on 32-bit CPU and was instead replaced with Arexx. If you want to run Amiga Basic programs on Amiga OS 2.0 or better you need to use another intepreter or compiler.

One of the most interesting things about the original Amiga Basic intepreter is that Microsoft created it, so I think this is was my first interaction with the Redmond Giant.

The Amiga Basic came with a couple of high end features

Subprograms had scope. In short, variables declared in a procedure were local to that procedure and not global.

You did not have to print out line numbers. The program would execute lines from top to bottom.

You could create labels where the program execution could jump to with names, and not numbers. This makes the program easier to maintain.

You could open files and write to files. You could even communicate on the RS232 serial port.

There was a rich library of Amiga functions where you could access Amiga specific features like SOUND, SAY, graphic libraries like LINE, CIRCLE, PAINT and OBJECT that you could use to create graphical animations.

I've also heard it rumored that you could inline assembler, and call assembler code directly, but this functionality was so buggy that it in the end was useless.

Your first program

We are now going to dive into code written for a language that has not been working with any hardware or operating system released last 25 years. However, you can still get a copy of Workbench 1.2 with the Extras disk from Amiga Forever, and with an emulator try out this fascinating programming language from Microsoft.

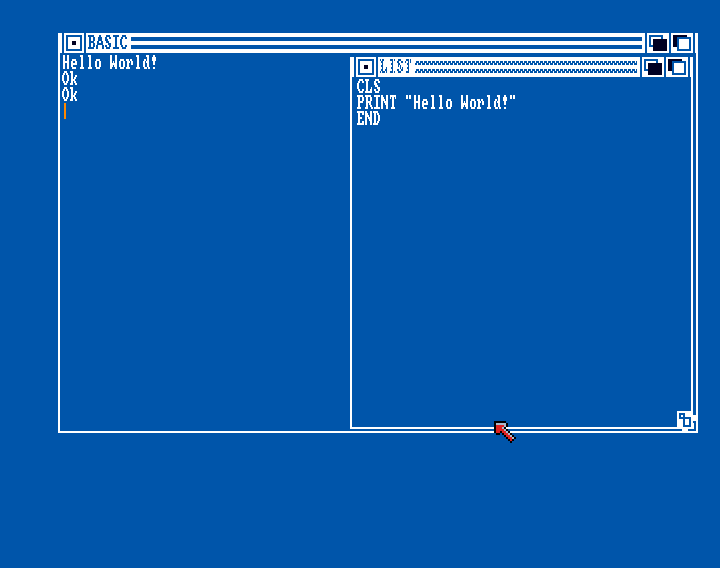

This is Hello World in Amiga Basic.

Clear the result window, print the text and end the program.

- CLS is the command to clear the result window.

- PRINT outputs text to the screen.

- END indicates the program is done. This is optional, when the list is EOF then the program is inded.

Ok Ok. Every time I save or bring up the LIST window the intepreter tells me "Ok".

Variables

In Amiga Basic you have floating point numbers, integers and strings.

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| float | Numbers with decimals: 3.0, -0.05, 3.14 |

| integer | Numbers: 3, 0, -345 |

| string | Multiple characters: "Hello World!", "Cheers!", "My dog is Sam" |

It is the declaration of the variable that decides what type it has. Float is the default type. You add a % suffix if you want an integer or a $ suffix for a string.

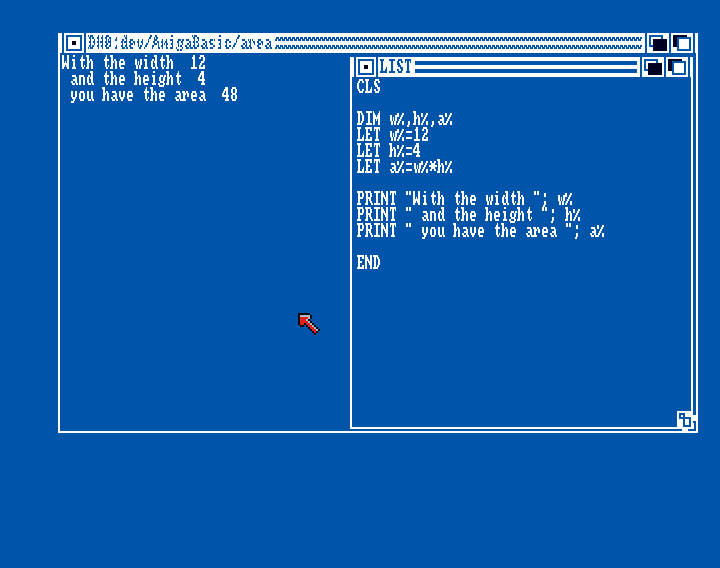

This program will calculate the area of a rectangle.

DIM w%,h%,a% LET w%=12 LET h%=4 LET a%=w%*h%

PRINT "With the width "; w% PRINT " and the height "; h% PRINT " you have the area "; a%

END

Here I specify explicitly that I want integers, even though it would have worked just as fine with the default value type, float.

- DIM can declare several variables on the same row. The %-suffix indicates they are integers.

- LET lets you assign values to variables

- PRINT lets you output several values on one row with

;

PRINT is a confusing command as it outputs spaces around identifiers. This makes output formatting very hard sometimes.

You can also have constants in your program and read them in as data. This is done with the commands DATA and READ.

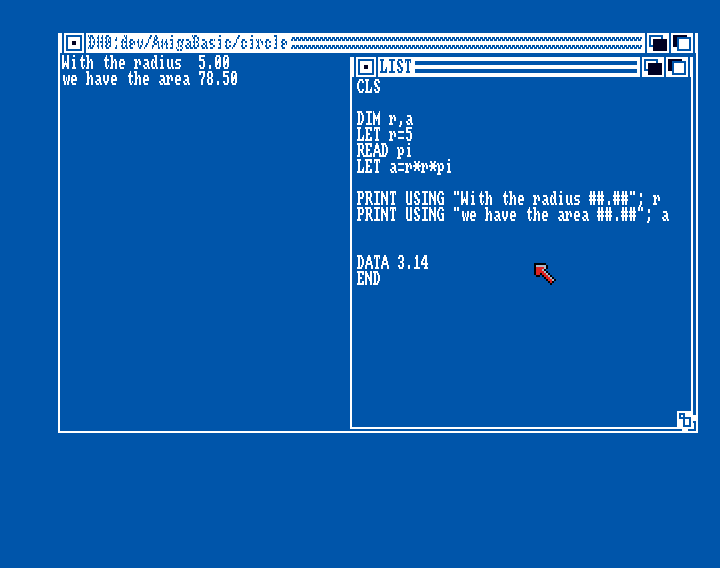

DIM r,a LET r=5 READ pi LET a=rrpi

PRINT USING "With the radius ##.##"; r PRINT USING "we have the area ##.##"; a

DATA 3.14 END

If you don't add enough of ## in the print using, you're going to get some nasty % characters by the intepreter.

- READ take the value from

DATAand put it in a variable called pi - PRINT USING defines a format where the number 5 will be shown as 5.00

- DATA constants that can be read by the program. This can appear anywhere in the code, but is most often put in the end.

In the LIST window I have two newlines before DATA. This is because the editor has a bug where you sometimes can't remove lines. It complains about the empty lines being too long.

Read input from user

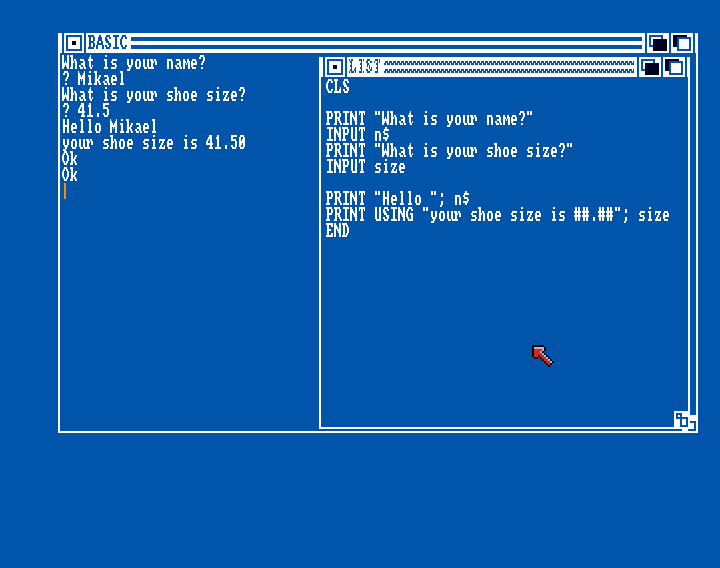

You use the keyword INPUT to read input from the user. This program will ask for you shoe size and print it back to you.

PRINT "What is your name?" INPUT n$ PRINT "What is your shoe size?" INPUT size

PRINT "Hello "; n$ PRINT "your shoe size is ##.##"; size END

This is actually the first program that I ever typed into the intepreter from a computer magazine called DatorMagazin3. The article was showing the same program in several different programming languages.

- INPUT declares a variable at the same time as assigning value from user input.

The INPUT command puts a questionmark before the user input and there is no way to modify this behavior.

Control flow

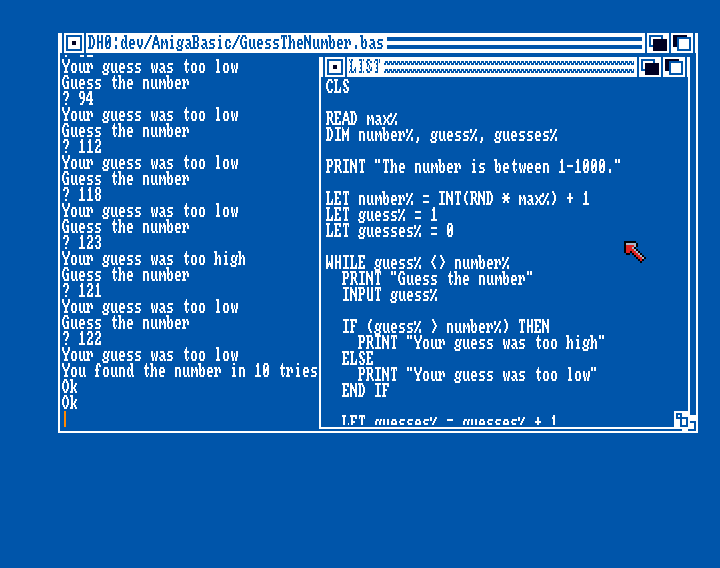

The amazing thing about Amiga Basic is that IF works with blocks. In older Basic dialects you only had the option to control flow by sending program execution to a specific label.

READ max% DIM number%, guess%, guesses%

PRINT "The number is between 1-1000."

LET number% = INT(RND * max%) + 1 LET guess% = 1 LET guesses% = 0

WHILE guess% <> number% PRINT "Guess the number" INPUT guess%

IF (guess% > number%) THEN PRINT "Your guess was too high" ELSE PRINT "Your guess was too low" ENDIF

LET guesses% = guesses% + 1 WEND

PRINT USING "You found the number in ## tries"; guesses% DATA 1000 END

I remember this being a learning exercise from the book "Turbovägen till Pascal" when I was learning Pascal.

- INT(RND * max%) Will return a random number between 0-999

- WHILE Will keep looping while the condition is true

- WEND Marks the end of the while block

RND will actually give us the same random sequence every time, so this game is not very fun after you've found out the number is always 122.

There is a bug in this code causing it to say our guess is too low, even when it is spot on. Can you propose a fix to that bug?

For-loop

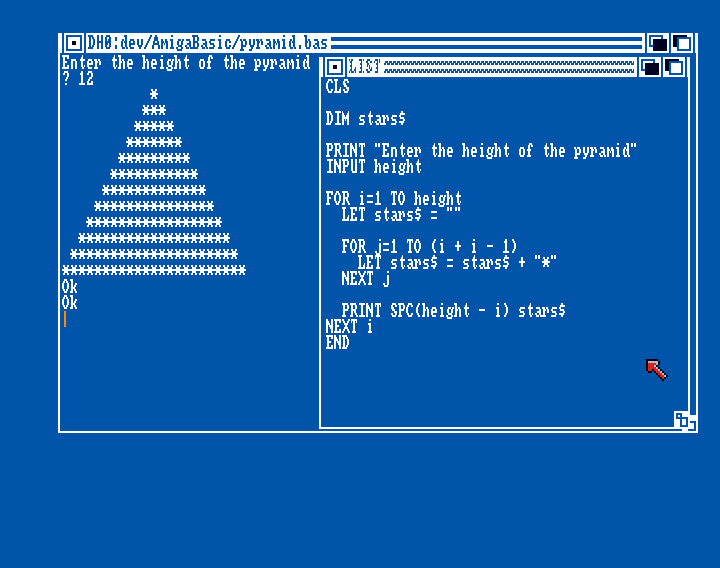

A foor loop starts at a number and counts up until it reaches max. This program will type out a pyramid of the height that you specify.

DIM stars$

PRINT "Enter the height of the pyramid" INPUT height

FOR i=1 TO height LET stars$ = ""

FOR j=1 TO (i + i - 1) LET stars$ = stars$ + "*" NEXT j

PRINT SPC(height - i) stars$ NEXT i END

- FOR initializers a counter at an index and runs until counter equals

TOargument - NEXT will increment the counter and return program execution to start of the FOR block

- SPC(height - i) will give

height - inumber of spaces to output in front of the stars

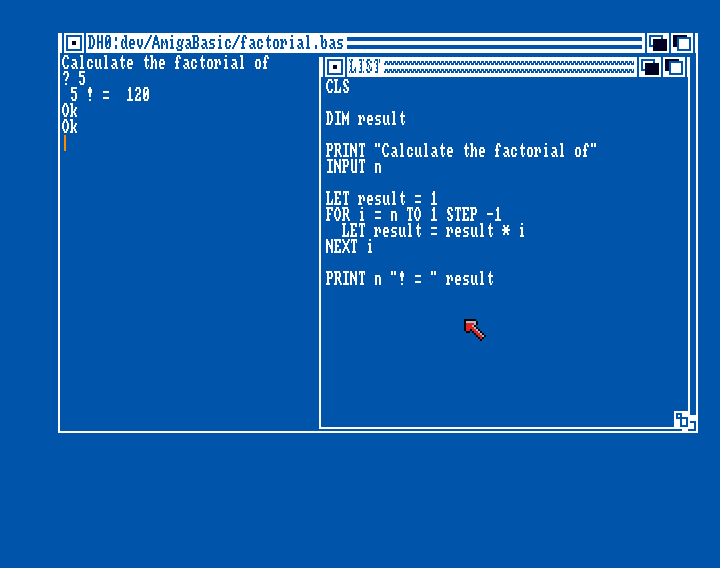

And we can also count down with the FOR loop. Here we use it to calculate the factorial of a number.

DIM result

PRINT "Calculate the factorial of" INPUT n

LET result = 1 FOR i = n TO 1 STEP -1 LET result = result * i NEXT i

PRINT n "! = " result END

- STEP -1 allows the FOR loop to count down instead of up.

Lucky we picked a small number. Who knows what will happen if the result variable overflows.

Strings

You define a string value by naming the identifier with a dollar sign $ in the end. There are some string functions built in to perform basic string operations.

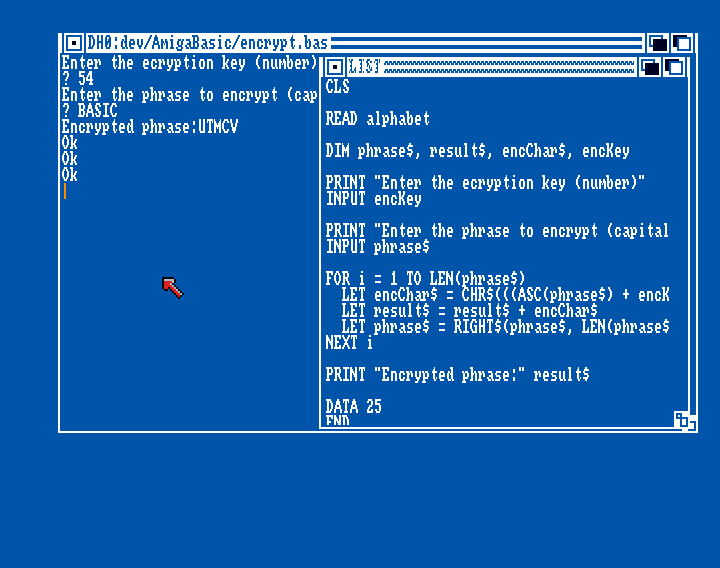

This program will take a number as encryption key, and a string, and with ceasar cifer encrypt the string.

READ alphabet

DIM phrase$, result$, encChar$, encKey

PRINT "Enter the encryption key (number)" INPUT encKey

PRINT "Enter the phrase to encrypt (capital letters) INPUT phrase$

FOR i = 1 TO LEN(phrase$) LET encChar$ = CHR$(((ASC(phrase$) + encKey) MOD alphabet) + ASC("A")) LET result$ = result$ + encChar$ LET phrase$ = RIGHT$(phrase$, LEN(phrase$) - 1) NEXT i

PRINT "Encrypted prase: " result$

DATA 25 END

I write my own encryption algorithm and I am proud of it.

- LEN(phrase$) returns the length of the string

- CHR(i) converts an ASCII number to string

- ASC(s$) returns the ASCII number for the string

- MOD is a modulus operator

- RIGHT$(phrase$, LEN(phrase$) - 1)

RIGHTpicks a number of characters from the right of a string. The whole expression will remove first character from a string.

Completely uncrackable.

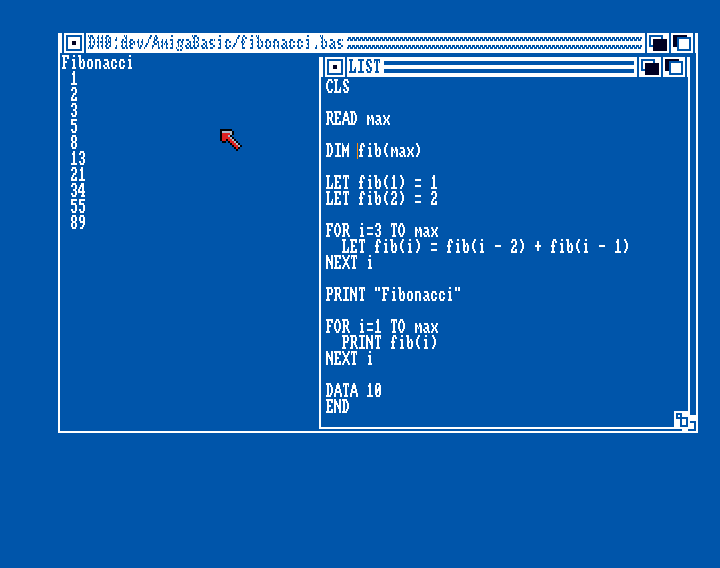

Arrays

Amiga Basic has no support at all for arrays, but you have direct access to the memory where you can read and write values as you please.

This program will calculate first 10 numbers from Fibonacci and output them to the screen.

READ max

DIM fib%(max)

LET fib(1) = 1 LET fib(2) = 2

FOR i=3 TO max LET fib(i) = fib(i - 2) + fib(i -1) NEXT i

PRINT "Fibonacci"

FOR i=1 TO max PRINT fib(i) NEXT i

DATA 10 END

- DIM fib%(max) You can dimension a variable with custom size.

- fib(1) And you can index into a position in a variable.

It is not arrays per se, but it will work well enough.

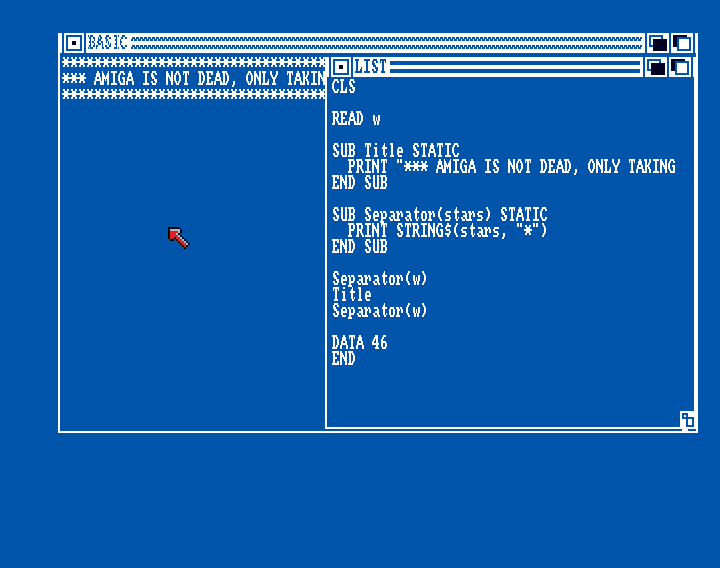

Procedures

Amiga Basic has this feature where you can split your program into sub programs. These sub programs have their own scopes meaning they do not share variables as labels do. This makes it easier to maintain.

READ w

SUB Title STATIC PRINT "*** AMIGA IS NOT DEAD, ONLY TAKING A BREAK ***" END SUB

SUB Separator(stars) STATIC PRINT STRING$(stars, "*") END SUB

Separator(w) Title Separator(w)

DATA 46 END

The SUB is not really a procedure in the traditional sense, but more seen as a sub program that you can send arguments to.

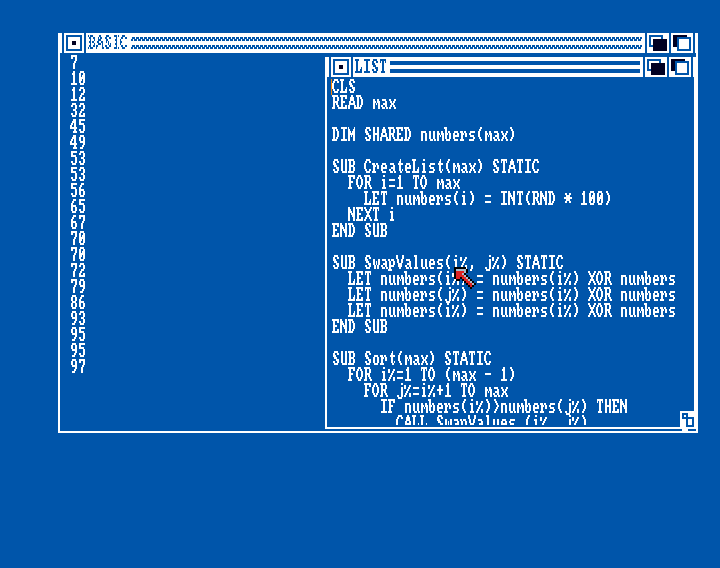

Here is another example performing a bubble sort

DIM SHARED numbers(max)

SUB CreateList(max) STATIC FOR i=1 TO max LET numbers(i) = INT(RND * 100) NEXT i END SUB

SUB SwapValues(i%, j%) STATIC LET numbers(i%) = numbers(i%) XOR numbers(j%) LET numbers(j%) = numbers(i%) XOR numbers(j%) LET numbers(i%) = numbers(i%) XOR numbers(j%) END SUB

SUB Sort(max) STATIC FOR i%=1 TO (max - 1) FOR j%=i%+1 TO max IF numbers(i%)>numbers(j%) THEN CALL SwapValues (i, j) END IF NEXT j% NEXT i% END SUB

SUB PrintList(max) STATIC FOR i=1 TO max PRINT numbers(i) NEXT i END SUB

CreateList(max) Sort(max) PrintList(max)

DATA 20 END

- DIM SHARED Makes the numbers array globally accessible

- CALL can be used to invoke SUB procedures

Closing comments

Since my first programming language was Pascal, I have never been a fan of Basic. When I was young I had a friend that did a lot of programming in QBasic (DOS) but I could never really get the hang of it. I simply liked Pascal better.

As a forensic excersise I find Amiga Basic to be quite fun to play around with. That is very much because it is an official Microsoft Basic implementation, and I don't think I've been this close to early Microsoft software before. That would be MS-DOS 6.0.

Microsoft Amiga Basic is missing some crucial parts that I need in a modern programming language.

I need to be able to define types, records or objects. Amiga Basic is bound to its default types, int, float and string.

Amiga Basic has a function construct but that does only allow 1 statement. I need functions that allow blocks of code for their body, and that works with recursion.

You can access and manipulate the memory directly which is insanely dangerous. However I would love a construct like

newto reserve memory space for data and a pointer to that memory space. That would enable us to create linked lists.Amiga Basic is an intepreted language, but it would be nice if you could create a library of procedures/functions that could be imported from other languages.

Of course there are still operations in the API that I haven't covered here, but I think this guide goes through the bulk of what you can do with the language. If you have any questions please ask them here and I will see if I can dig out an answer from the reference material.

Thank you!

Footnotes

-

I will never get over that my father threw away his books on IBM-DOS 3 and COBOL85. Those things are unforgivable. ↩

-

I find it curious that most of these old computers shipped with a way to program them, often some sort of BASIC clone. You were not dependent on others to create programs for you, but you could create them yourself. ↩

-

DatorMagazin was a computer magazine about C64 and Amiga in the 80/90's. The imaginative name means literaly "computer magazine" in English. ↩